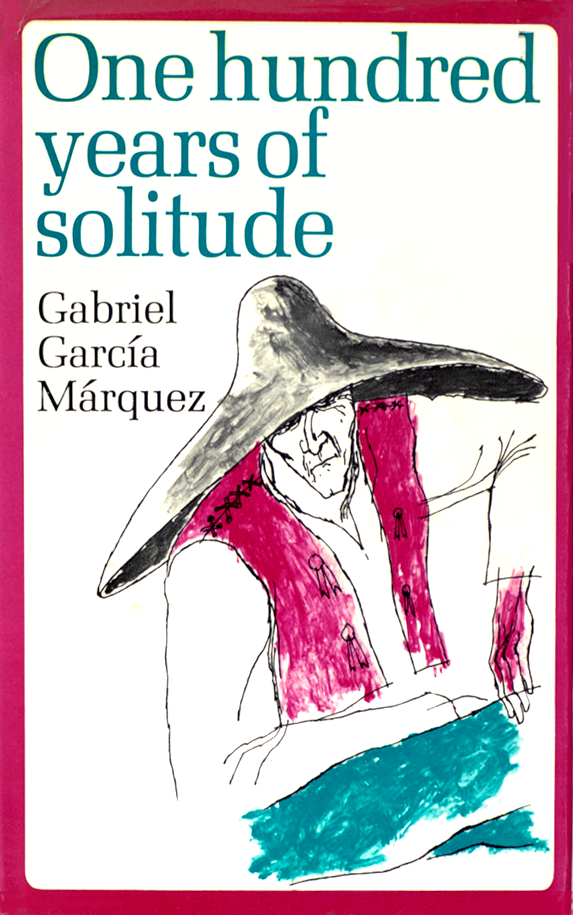

A Deep Dive into One Hundred Years of Solitude: Themes, Style, and Legacy

Discover the themes, style, and lasting influence of Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude in this 800-word deep-dive.

Introduction to a Literary Landmark

Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, first published in 1967, stands as one of the most influential novels of the twentieth century. Blending political commentary, family saga, and the shimmering possibilities of magical realism, the book chronicles the rise and fall of the Buendía family in the fictional town of Macondo. More than half a century later, readers and critics continue to return to its pages, searching for insights into Latin American history, human nature, and the blurred line between myth and reality.

The Birth of Macondo and Magical Realism

At the heart of the novel lies Macondo, a settlement that begins as an Edenic backwater and ends as a desolate ruin erased from maps and memories. Márquez presents Macondo’s transformation in language that shifts effortlessly between the ordinary and the fantastical. A swarm of yellow butterflies accompanies the illicit passion between Renata Remedios and Mauricio Babilonia; ghosts share kitchen tables with the living; insomnia causes villagers to lose their memories. These surreal images are not flights of fancy meant to distract the reader but carefully woven threads that expose deeper truths about colonialism, progress, and collective amnesia. The technique has come to be known as magical realism, and One Hundred Years of Solitude remains its defining example.

Cycles of History and the Buendía Family Tree

Another compelling layer is the novel’s cyclical structure. The Buendías seem destined to repeat mistakes across generations: obsessive quests for knowledge, ill-fated romances, and an enduring prediction that a child born with a pig’s tail will signal their doom. This repetition mirrors the turbulent history of Latin America, where revolutionary hopes often circle back to authoritarian realities. By the time readers reach the final pages, they realize that the Buendías’ fate was inscribed from the beginning, suggesting that those who fail to remember the past are condemned to relive it.

Key Characters to Know

• José Arcadio Buendía – the visionary founder of Macondo whose scientific curiosity borders on madness.

• Úrsula Iguarán – the pragmatic matriarch who anchors the family with resilience and foresight.

• Colonel Aureliano Buendía – the embodiment of political revolt, leading 32 uprisings only to face solitude in old age.

• Amaranta, Remedios the Beauty, and other memorable figures who represent desire, innocence, and spirituality.

Themes of Solitude, Love, and Memory

The word “solitude” in the title is far from decorative; it captures the spiritual isolation that clings to every Buendía. Whether through José Arcadio’s alchemical obsessions, Colonel Aureliano’s endless wars, or Fernanda del Carpio’s suffocating piety, each character seeks connection yet drifts into loneliness. Love surfaces as a possible antidote but often arrives too late or in forms society deems taboo. Márquez hints that memory, shared truthfully, could break the cycle, yet even memory succumbs to the erasures of time, war, and colonial rule. These interlocking themes bestow universal relevance on a story rooted in a very specific cultural context.

Political and Cultural Context

Reading the novel without understanding mid-century Latin American politics is like visiting Macondo blindfolded. The banana company massacre echoes the real-life 1928 tragedy in Colombia, reminding readers that capitalist exploitation and governmental complicity are not fictional exaggerations. Colonel Aureliano’s libertarian wars parallel the continent’s repeated flirtations with both revolution and dictatorship. By embedding these events in a mythic setting, Márquez allows local histories to resonate with global readers, ensuring the novel’s longevity on university syllabi and bestseller lists alike.

Stylistic Brilliance: Language, Structure, and Symbolism

Márquez’s prose, brilliantly translated into English by Gregory Rabassa, is both lush and disciplined. Sentences spiral on for half a page yet never feel bloated; they mimic the oral storytelling traditions of Caribbean villages. The novel’s non-linear chronology demands active participation, compelling readers to piece together genealogies and timelines. Symbols such as yellow flowers, gypsy caravans, and recurrent names (José Arcadio, Aureliano, Amaranta) create a tapestry that is at once intricate and accessible. The result is a reading experience that feels as though it could stretch beyond the printed page, echoing inside the reader’s imagination long after the book is closed.

Global Impact and Enduring Legacy

One Hundred Years of Solitude sold millions of copies within years of release and played a pivotal role in earning García Márquez the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature. Its success helped usher in the “Boom” of Latin American literature, elevating voices such as Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Carlos Fuentes to international prominence. Beyond literature, the novel has influenced filmmakers, painters, and even political movements seeking to articulate a uniquely Latin American modernity. It continues to appear on lists of the greatest books ever written, loved equally by casual readers and scholars.

Why the Novel Still Matters Today

In an era of rapid technological change and social fragmentation, the questions Márquez raises—about memory’s fallibility, the cost of unchecked ambition, and the human yearning for meaning—feel freshly urgent. Macondo could be any community grappling with globalization, environmental degradation, or historical trauma. The novel encourages readers to confront uncomfortable truths while retaining faith in storytelling’s power to preserve culture and provoke empathy. That dual function makes One Hundred Years of Solitude not just a classic but a living text, ready to guide new generations through the labyrinth of history.

Tips for First-Time Readers

If you are approaching the novel for the first time, keep a family tree nearby; similar names can cause confusion. Read unhurriedly and allow the magical elements to coexist with political realities—they are two halves of the same truth. Finally, revisit the book after some time; each reading uncovers fresh layers, proving that solitude, paradoxically, can forge deeper connections across time, culture, and language.

Conclusion

From its opening sentence—"Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember the distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice"—Gabriel García Márquez invites readers into a universe where the fantastic and the familiar dance in perpetual motion. By the time the final cyclonic wind sweeps Macondo off the map, we realize that the Buendías’ saga mirrors our own search for belonging, purpose, and, ultimately, liberation from solitude. That timeless resonance secures One Hundred Years of Solitude a place not merely on bookshelves but in the collective consciousness of world literature.