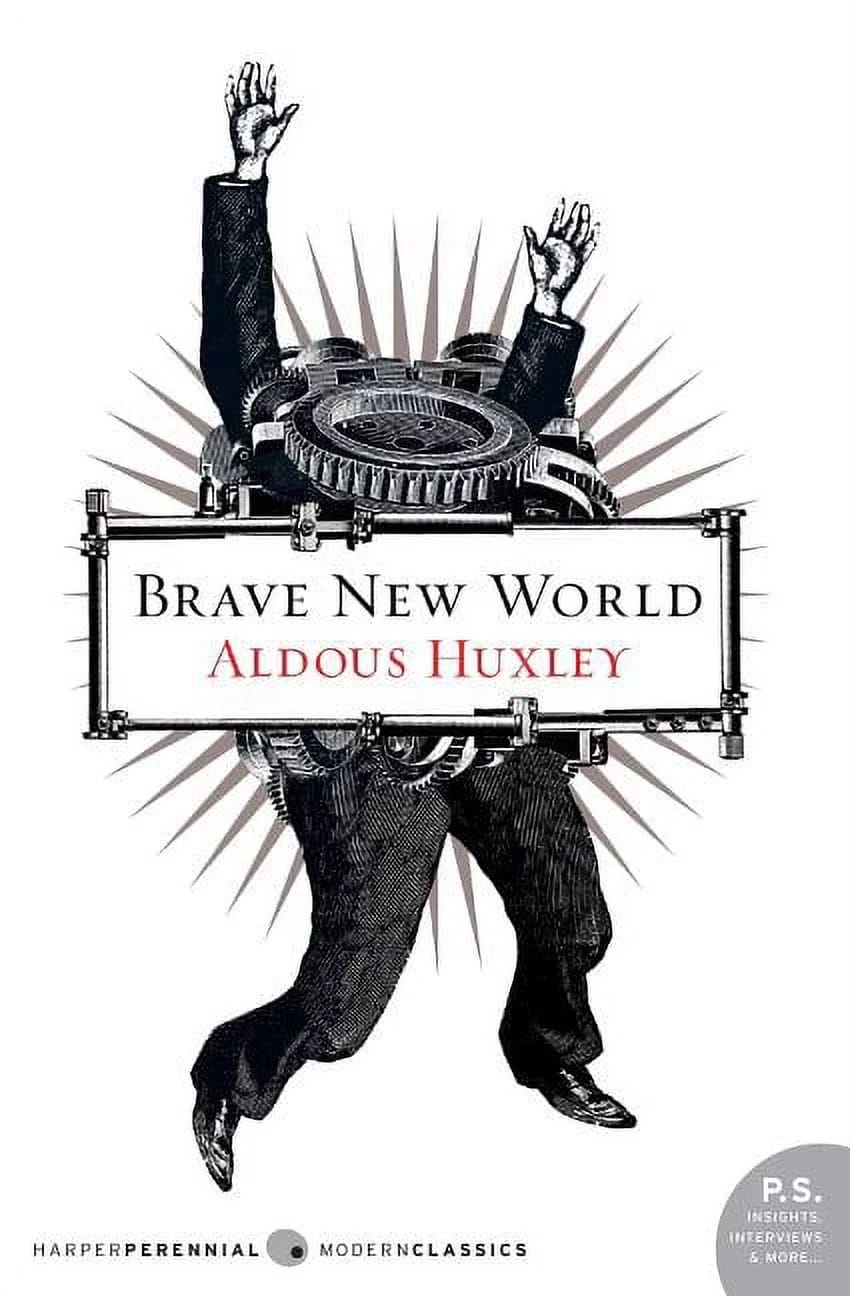

Brave New World: A Visionary Warning for Our Times

In-depth look at Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, covering plot, themes, characters, and why this 1932 dystopia still resonates today.

Introduction to Brave New World

Published in 1932, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World remains one of the most unsettling yet prescient works of dystopian fiction. Written in the shadow of the Fordist assembly line and the rise of totalitarian ideologies, the novel imagines a future society where technological efficiency and social stability outrank freedom, art, and authentic emotion. Huxley’s creative blend of satire, science, and social commentary asks readers to question which comforts are worth sacrificing to remain truly human, making the work as relevant today as it was nine decades ago.

Plot Summary

Set in the year 632 A.F. (After Ford), the World State has eradicated war, poverty, and disease—but at a morally staggering cost. Citizens are genetically engineered in vast Hatcheries, conditioned through sleep-learning, and kept docile with the happiness drug soma. Into this chemically tranquil society strides Bernard Marx, an Alpha Plus who feels out of step with the system. His trip to a “Savage Reservation” exposes him to John, a naturally born man who was raised on Shakespeare instead of state slogans. When John returns with Bernard to London, his passionate rejection of artificial pleasure forces everyone, from ordinary Gammas to the all-powerful Controller Mustapha Mond, to confront uncomfortable truths about their supposedly perfect world.

Main Characters

Huxley populates his novel with characters designed to personify competing worldviews. Bernard Marx yearns for individual significance but lacks the courage to seize it. Lenina Crowne, a cheerful Beta, embodies the seductive ease of conformity. Helmholtz Watson represents a restless creative spirit stifled by state orthodoxy. John “the Savage,” the novel’s moral center, illustrates the pain and beauty of genuine human experience. Finally, Mustapha Mond serves as philosopher-king, articulating the cold logic behind a system that trades art, religion, and love for comfort and order.

Key Themes

Mass Production and Consumerism

The worship of Henry Ford signals a society built on the conveyor belt. People, leisure activities, even emotional responses are churned out like identical Model T’s. Huxley foresaw a world where obsolescence is manufactured, keeping citizens in a perpetual cycle of consumption—a critique that echoes in today’s fast-fashion trends and planned device upgrades.

Control Through Pleasure

Unlike Orwell’s vision of overt oppression, Huxley’s rulers maintain power not with fear but with pleasure. Soma, feel-good games, and erotic play erase any impulse to rebel. This theme anticipates modern debates on algorithm-driven entertainment and pharmaceutical solutions that numb discontent instead of addressing its causes.

Loss of Individuality

From birth, each citizen is pre-destined for a caste and molded to love that role. Individual aspiration is branded antisocial. Huxley warns that when society values stability above all, uniqueness becomes a threat; the resulting homogeneity impoverishes art, inquiry, and empathy.

Symbolism and Motifs

Soma symbolizes escapism, while the repetitive chant “Ending is better than mending” critiques throwaway culture. Shakespeare’s plays, quoted by John, represent the richness of the human spirit that the World State has purged. Even the alphabetized caste names—Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Epsilon—reduce people to inventory, reinforcing the novel’s mechanized aura.

Relevance to the 21st Century

Huxley’s speculative technology—genetic engineering, mood-altering drugs, targeted advertising—now hovers on the edge of, or fully inside, our reality. CRISPR gene editing raises ethical dilemmas similar to the Hatcheries’ designer embryos. Social media’s dopamine loops echo soma’s instant gratification. In workplaces, metrics can matter more than meaning, echoing the World State’s devotion to productivity. Each parallel underscores the urgency of deliberating technological progress before convenience silently erodes autonomy.

Comparisons With Other Dystopias

While George Orwell’s 1984 depicts tyranny through surveillance and brutality, Huxley envisions a softer despotism where citizens sign away freedom for pleasurable distractions. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale explores control via fundamentalism, contrasting Huxley’s secular utilitarianism. Reading these works together enlarges our understanding of the multifaceted threats that can undermine a free society, whether through force, faith, or fun.

Conclusion

More than a cautionary tale, Brave New World is a mirror reflecting our hopes and vices. It nudges us to ask difficult questions: How much convenience is too much? When does safety suffocate the soul? By dramatizing the trade-offs between happiness and humanity, Huxley invites readers to become vigilant stewards of their own destinies. As technology accelerates and consumer culture deepens, his visionary warning grows only louder, urging each new generation to choose freedom over fashionable chains.