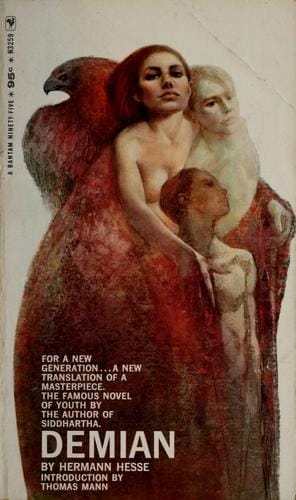

Demian: Unraveling Hermann Hesse’s Visionary Coming-of-Age Novel

Explore Hermann Hesse’s “Demian”—plot summary, major themes, symbols, and its lasting impact on modern readers seeking authentic self-discovery.

Introduction to Demian

Published in 1919, Hermann Hesse’s “Demian: The Story of Emil Sinclair’s Youth” remains one of the most intriguing bildungsromans of the twentieth century. Blending psycho-spiritual exploration with gripping narrative, the novel follows young Emil Sinclair as he grapples with moral dichotomies, identity, and the intoxicating pull of self-realization. This article offers an 800-word deep dive into the plot, themes, symbols, and lasting cultural impact of “Demian,” helping new readers and seasoned Hesse enthusiasts alike appreciate its multi-layered brilliance.

Plot Overview

“Demian” opens with Emil Sinclair recalling a formative childhood incident: to impress older boys, he invents a lie that entangles him in blackmail. Rescued by the enigmatic Max Demian, Sinclair begins a friendship that upends his sheltered worldview. As the years pass, Sinclair drifts between the ‘world of light,’ represented by familial security and conventional religion, and the ‘world of darkness,’ where instinct, desire, and authenticity reside. Guided intermittently by Demian’s provocative teachings, Sinclair experiments with rebellion, art, alcohol, and romantic longing. Ultimately, he learns to heed his inner voice—symbolized by the mystical god Abraxas—culminating in a visionary battlefield scene that merges personal awakening with the collective convulsions of pre-World War I Europe.

Main Characters

Emil Sinclair

Sinclair narrates the story in confessional style, chronicling his evolution from frightened schoolboy to introspective young adult. His internal struggle personifies humanity’s universal quest for wholeness.

Max Demian

Charismatic, intellectually fearless, and somewhat otherworldly, Max Demian operates as Sinclair’s mentor and mirror. Whether Demian is flesh-and-blood or a projection of Sinclair’s higher self remains deliberately ambiguous.

Pistorius

The eccentric organist introduces Sinclair to Gnosticism and the syncretic deity Abraxas, reinforcing the notion that good and evil are inseparable facets of a single cosmic force.

Frau Eva

Demian’s mother, Frau Eva, embodies the archetype of the divine feminine. Sinclair’s reverence and romantic yearning for her signal his readiness to integrate intuition with intellect.

Key Themes

Duality and the Search for Self

The novel’s central tension lies between the prescribed morality of Sinclair’s upbringing and the darker impulses he feels within. Hesse argues that authentic maturity requires acknowledging, rather than suppressing, our shadow side.

Spiritual Rebellion

Sinclair’s embrace of Abraxas reflects a break from binary, church-taught ethics toward a spirituality that accommodates contradiction. This theme resonated with post-war readers disillusioned by traditional institutions.

Individuation

Influenced by Carl Jung, Hesse illustrates individuation—integrating conscious and unconscious elements—as a heroic journey. Demian and Frau Eva function as anima and animus guides leading Sinclair toward psychic wholeness.

The Mentor Archetype

From Demian’s Socratic questioning to Pistorius’s arcane lectures, mentors in the novel catalyze Sinclair’s metamorphosis. Yet Hesse stresses that true guidance ultimately comes from within.

Symbolism and Motifs

The sparrow hawk breaking free of its egg becomes the book’s signature image, emblazoned on a painting Sinclair makes after a dream. It signifies the painful but necessary rupture of old shells—beliefs, fears, and societal expectations—that confine personal growth. The biblical story of Cain and Abel is reinterpreted by Demian to question superficial labels of ‘good’ and ‘evil.’ Abraxas, a deity encompassing light and darkness, challenges the dualism rooted in Western thought. Finally, music and art act as portals that allow Sinclair to commune with his subconscious.

Historical and Cultural Impact

Released under the pseudonym “Emil Sinclair” to sidestep controversy, “Demian” struck a chord with Germany’s Lost Generation and, later, the counterculture movements of the 1960s. Its fusion of Eastern mysticism, Jungian psychology, and Christian symbolism anticipated the era’s psychedelic and transcendental philosophies. Musicians from the Beatles to David Bowie cited Hesse as inspiration, while contemporary novels such as Paulo Coelho’s “The Alchemist” echo Hesse’s themes of destiny and inner calling.

Why Demian Still Matters

Modern readers navigating social media pressures, polarized politics, and identity debates will find Sinclair’s dilemma strikingly familiar. Hesse’s insistence that individuality need not exclude compassion offers a roadmap for ethical, self-aware living in an age of noise. Moreover, the novel’s compact length—under 160 pages in most editions—makes it an accessible entry point into classic literature without sacrificing depth.

Tips for First-Time Readers

1) Keep a journal to track recurring symbols; the act of noting dreams, hawks, and biblical references mirrors Sinclair’s own self-analysis. 2) Read slowly; Hesse’s lyrical prose conceals philosophical questions that reward reflection. 3) Explore companion texts such as Jung’s essays on individuation to enrich understanding. 4) Discuss with others; “Demian” invites multiple interpretations, and conversation often reveals overlooked layers.

Conclusion

“Demian” endures because it dramatizes an inner revolution that every generation must reenact: the passage from borrowed morality to self-defined truth. By following Emil Sinclair’s odyssey under the guidance of the mysterious Demian, readers confront their own unintegrated shadows and emergent potentials. More than a coming-of-age story, Hesse’s novel is a timeless meditation on freedom, responsibility, and the sacred task of becoming fully oneself.