Exploring 'A Wizard of Earthsea': Themes, Characters, and Legacy

Discover the plot, themes, characters, and lasting legacy of Ursula K. Le Guin's fantasy masterpiece A Wizard of Earthsea in this in-depth, spoiler-light review.

Introduction to a Fantasy Milestone

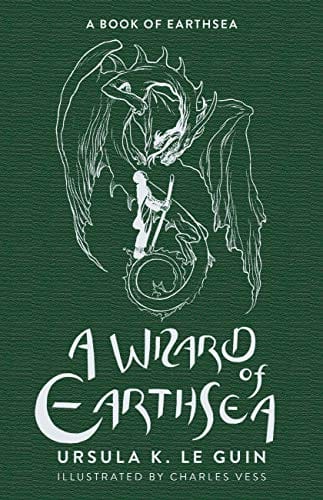

"A Wizard of Earthsea," first published in 1968, marks the beginning of Ursula K. Le Guin’s beloved Earthsea Cycle. At once a coming-of-age tale, a meditation on power, and a poetic exploration of balance, the novel has become required reading for anyone serious about fantasy literature. Long before sprawling franchises dominated booklists, Le Guin proved that epic storytelling could be intimate, philosophical, and deeply human. More than fifty years later, the journey of the young mage Ged still resonates, inviting fresh generations of readers to the archipelago world of Earthsea.

Because Le Guin foregrounds language, myth, and the limits of ambition, "A Wizard of Earthsea" holds a unique position between classic hero quests and modern character-driven fiction. The novel’s thoughtful pace, spare prose, and focus on true names distinguish it from the battle-heavy sagas that would flourish in later decades. Yet its influence can be felt across modern fantasy, from the school-for-magicians trope to nuanced depictions of magic as a moral burden.

Concise Plot Summary

The story follows Ged, a talented yet headstrong boy from the island of Gont. Discovered by the wandering mage Ogion, he is sent to the wizard school on Roke to shape his raw power. There, a reckless display of skill unleashes a nameless shadow that threatens both Ged’s life and the cosmic equilibrium of Earthsea. Realizing that no master can handle the evil he has summoned, Ged leaves the school to pursue the shadow himself, journeying from port towns to desolate oceans in a desperate bid for redemption. Ultimately, he must name the shadow and accept it as part of himself, a revelation that enables him to restore balance and return home wiser, humbler, and truly free.

Key Themes and Motifs

The Balance of Power

Central to Earthsea is the concept of Equilibrium: every act of magic disturbs the natural order and must therefore be employed with restraint. Through Ged’s mistakes, Le Guin critiques youthful bravado while underscoring ecological and spiritual interdependence. The idea that power carries consequences foreshadows modern conversations about sustainability and responsibility.

True Names and Identity

Le Guin’s magical system rests on the Old Speech, a language in which each thing’s true name grants control over it. Knowing one’s own name becomes synonymous with understanding one’s inner nature. When Ged finally names the shadow, he is, in effect, recognizing the dark half of his identity. The motif invites readers to reflect on self-knowledge as a prerequisite for maturity.

Fear, Shadow, and Acceptance

The shadow Ged releases is more than a monster; it embodies his pride, fear, and potential for evil. Rather than destroy it, he must integrate it. The novel thus dramatizes Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow self years before the term gained mainstream popularity, reinforcing the psychological depth that sets "A Wizard of Earthsea" apart from many sword-and-sorcery contemporaries.

Main Character Analysis

Ged (whose use-name is Sparrowhawk) begins as a small-town goat herder craving recognition. Gifted beyond his peers, he fears insignificance and compensates with arrogance. His bitter rivalry with fellow student Jasper becomes the catalyst for the fateful summoning. By novel’s end we witness a profound transformation: Ged evolves from proud prodigy to servant of balance. His arc demonstrates that true greatness lies not in domination but in restraint and understanding.

Supporting characters, though given less page time, enrich the narrative. Ogion embodies patience and harmony with nature, acting as a thematic foil to the impulsive boy he mentors. Vetch, Ged’s loyal friend, models unconditional support, emphasizing community over competition. Even the dragons of Pendor serve a symbolic purpose, representing untamed power and the peril of false names.

World-Building and the Magic System

The Earthsea archipelago consists of hundreds of islands, each with distinct cultures, dialects, and economies. Instead of medieval kingdoms, Le Guin offers maritime societies that live and die by the sea’s rhythms. This geography enables rich metaphors about isolation and connection: water separates islands yet also links them. The map printed at the book’s front has guided countless readers on imaginary voyages and influenced later fantasy cartography.

Magic in Earthsea is methodical and linguistic. Wizards study on Roke to learn the Old Speech, memorize runes, and practice weatherworking, illusion, and transformations. Because every spell disrupts equilibrium, practitioners must weigh necessity against cost. This intellectual approach makes wizardry feel both believable and wondrous, avoiding the deus ex machina pitfalls that plague looser systems.

Literary Style and Narrative Voice

Le Guin writes in lyrical yet economical prose reminiscent of oral storytelling. Each sentence feels carved rather than poured, reflecting her background in anthropology and linguistics. The omniscient narrator employs a mythic distance that lends the story timeless resonance while still granting intimate access to Ged’s inner turmoil. Frequent references to songs, proverbs, and histories create the sense that readers are merely dipping into a much larger cultural ocean.

The novel’s concise length—barely 200 pages—demonstrates that epic stakes do not require epic word counts. By stripping away filler, Le Guin keeps focus on moral evolution. Her stylistic choices have inspired authors such as Neil Gaiman, N. K. Jemisin, and Patrick Rothfuss, who praise her ability to balance grandeur with emotional clarity.

Legacy and Influence

"A Wizard of Earthsea" predates many fantasy cornerstones, including "The Sword of Shannara," "The Belgariad," and even Dungeons & Dragons. Its portrayal of a magic school set precedent long before Hogwarts. More importantly, Le Guin challenged genre norms by featuring a protagonist with dark skin in a time when most fantasy defaulted to Eurocentric casts. Though early cover art often whitewashed characters, later editions and adaptations have reclaimed Earthsea’s multicultural essence.

The novel has been translated into dozens of languages, adapted for radio, television, and graphic novels, and continues to appear on school curricula worldwide. Critics regularly cite it alongside "The Lord of the Rings" and "The Chronicles of Narnia" as foundational to modern fantasy yet distinct in tone and philosophy.

Why Read “A Wizard of Earthsea” Today?

For new readers, Ged’s journey offers an enduring lesson: mastering oneself is more heroic than conquering others. Seasoned fantasy fans will appreciate the narrative’s subtle subversions of genre expectations. Educators find the novel a rich springboard for discussions about ecology, identity, and ethics. Whether enjoyed as a standalone adventure or the gateway to the broader Earthsea Cycle, the book rewards careful reading and rereading.

Moreover, in an era grappling with planetary imbalance and social fragmentation, Le Guin’s vision of equilibrium feels strikingly relevant. Her insistence that words shape reality resonates in today’s information-saturated world, reminding us that language, like magic, should be wielded responsibly.

Conclusion

"A Wizard of Earthsea" endures because it marries spellbinding adventure with profound psychological and philosophical insight. Ursula K. Le Guin crafted a fantasy classic that transcends escapism, inviting readers to confront their own shadows and strive for harmony with the world around them. If you seek a novel that challenges, delights, and lingers long after the final page, set sail for Earthsea and discover why Ged’s story continues to shape the contours of imaginative literature.