Exploring Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire”: Themes, Characters, and Lasting Impact

Explore "A Streetcar Named Desire" through plot, characters, themes, and legacy in this 800-word guide to Tennessee Williams’ enduring masterpiece.

Introduction

Since its electrifying Broadway debut in 1947, Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” has captivated audiences with its raw exploration of survival, sexuality, and the fragile borders that separate illusion from reality. This Pulitzer Prize–winning play remains a cornerstone of American drama, continually revived on stage and screen for its lyrical language, complex characters, and unflinching portrait of a society in transition. From the steamy streets of New Orleans to classrooms across the globe, Williams’ masterpiece invites readers and viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about power, class, and the masks we wear to outlast despair.

Plot Overview

The narrative follows displaced Southern belle Blanche DuBois, who arrives at the cramped French Quarter apartment of her sister Stella and Stella’s husband, Stanley Kowalski. Blanche carries little more than fading glamour, a trunk of frayed finery, and a mounting sense of panic over her lost ancestral home, Belle Rêve. Stanley, a proud working-class veteran, immediately mistrusts Blanche’s airs and digs for the secrets behind her sudden visit. Over a blistering summer, Stanley’s aggression and Blanche’s instability clash in scenes alternately tender and violent, culminating in Blanche’s mental breakdown and forced removal to an asylum, while Stella remains torn between loyalty to her sister and her passion for Stanley.

Key Characters

Blanche DuBois: A once-privileged schoolteacher whose tragic past and desperate need for validation propel much of the drama. Her cultivated speech, delicate manners, and constant desire for flattering light contrast sharply with the gritty environment of Elysian Fields. Bluffing through lies about her age and circumstances, she represents the Old South’s fading grandeur and the precariousness of identity built on deception.

Stanley Kowalski: Brash, virile, and fiercely territorial, Stanley embodies the post-war American ethos of rugged individualism. His blunt dialogue, obsession with poker, and forceful presence highlight a new social order that values raw power over inherited status. Yet his cruelty toward Blanche reveals deeper insecurities about class and control.

Stella Kowalski: Caught between past and present, Stella chooses marital desire over familial duty. Her ability to navigate Stanley’s volatility with understated resilience gives the play emotional depth, illustrating how love can blur moral clarity.

Mitch: Stanley’s gentler friend offers Blanche a fleeting chance at redemption. His courtship underscores her longing for safety, but when Stanley exposes her history, Mitch’s rejection seals Blanche’s fate.

Major Themes

Illusion vs. Reality

Williams weaves the tension between truth and fantasy into every scene. Blanche bathes obsessively to “wash away” her past and hides within lamplight that diffuses harsh truths about her age. Stanley, conversely, bulldozes illusions, brandishing papers that reveal Belle Rêve’s foreclosure and Blanche’s scandals. Their collision underscores the psychological cost of sustaining illusion in a world that prizes authenticity.

Class Conflict

The downfall of the genteel DuBois lineage and the ascendance of immigrant-descended Stanley dramatize a post-Civil War social reshuffling. Blanche clings to etiquette and French phrases, yet she is financially destitute; Stanley, sweating in a sleeveless shirt, wields economic and physical power. Their antagonism mirrors a larger national shift from plantation privilege to industrial pragmatism.

Gender and Power

“A Streetcar Named Desire” critiques mid-twentieth-century gender norms. Stanley asserts dominance through sexuality and violence, exemplified in the infamous poker-night quarrel and the climactic assault on Blanche. Meanwhile, Blanche leverages femininity as survival, flirting to secure protection. Stella’s decision to remain with Stanley after the assault reflects the societal pressure on women to prioritize domestic stability over personal justice.

Symbolism and Motifs

The titular streetcar, eternally rumbling through New Orleans, symbolizes the inexorable pull of desire that propels characters toward both pleasure and ruin. Light functions as another powerful motif: Blanche’s aversion to bright illumination reveals her fear of exposure, while Stanley’s act of ripping the paper lantern off the bulb metaphorically destroys her illusion. Music, especially the “Varsouviana” polka that haunts Blanche, underscores her trauma over her young husband’s suicide, surfacing at moments of heightened stress.

Historical and Cultural Context

Premiering shortly after World War II, the play reflects anxieties about changing gender roles, the decline of aristocratic traditions, and the rise of working-class assertiveness. New Orleans—a melting pot of cultures, races, and moral codes—provides a fertile backdrop for these tensions. Williams, drawing on his own experiences with mental illness in the family and the repression of queer identity, imbues the script with autobiographical nuance that challenges mid-century taboos.

Stagecraft and Cinematic Adaptations

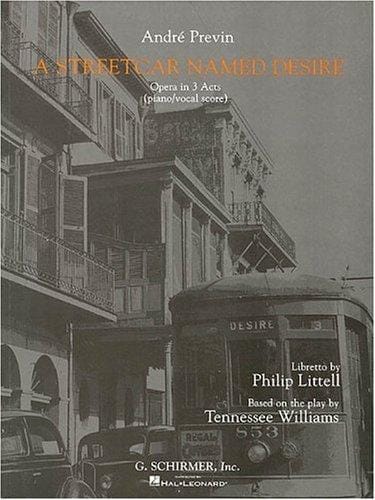

Elia Kazan’s original Broadway staging emphasized naturalistic acting, tight interior spaces, and innovative use of offstage sounds—like the looming streetcar—to heighten realism. The 1951 film adaptation, starring Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando, further immortalized the story, bringing Method acting into mainstream cinema. Subsequent revivals—featuring stars from Jessica Lange to Gillian Anderson—continue to experiment with multicultural casting, minimalist sets, and even immersive productions, demonstrating the play’s flexibility and ongoing relevance.

Lasting Impact on Modern Drama

Williams’ poetic dialogue, unfiltered exploration of sexuality, and fusion of realism with expressionistic devices paved the way for later playwrights such as Arthur Miller, Edward Albee, and August Wilson. Themes of mental health and domestic violence that once shocked viewers are now integral to contemporary storytelling, owing much to Williams’ groundbreaking candor. The character of Blanche, in particular, has become a benchmark for actors seeking roles that demand vulnerability, complexity, and emotional range.

Conclusion

More than seven decades after its premiere, “A Streetcar Named Desire” persists as a powerful mirror reflecting society’s evolving attitudes toward class, gender, and truth. Its unforgettable characters, lush symbolism, and suspenseful narrative invite each new generation to question where illusion ends and authenticity begins. Whether encountered on the page, stage, or screen, Tennessee Williams’ masterpiece continues to ride the unstoppable streetcar of desire—its whistle echoing with the promise and peril of the human condition.