I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki – Book Review & Cultural Insight

A compassionate review of Baek Se-hee’s memoir “I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki,” exploring depression, comfort food, and the hope found in small rituals.

Introduction

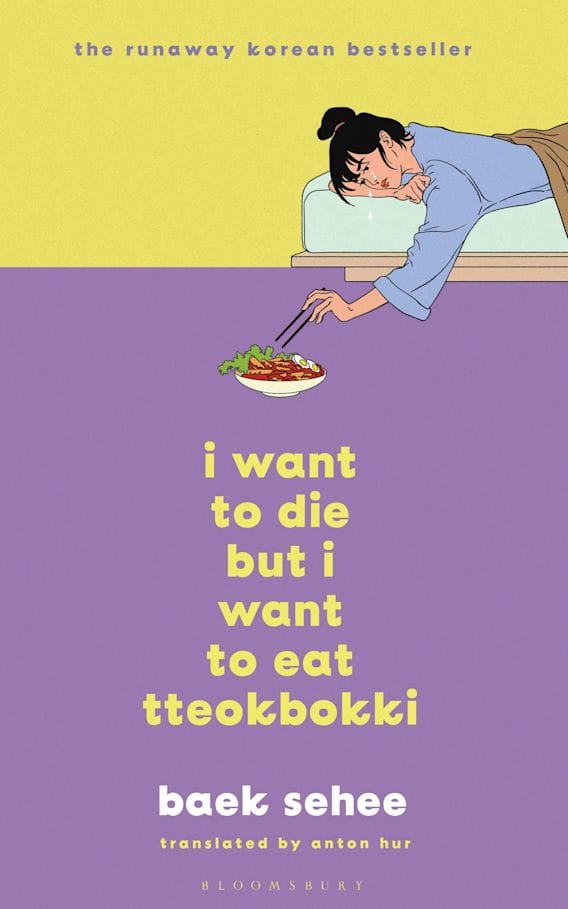

South Korean writer Baek Se-hee did not set out to pen an ordinary self-help guide. Instead, her breakout memoir, “I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki,” captures ten recorded therapy sessions that trace her quiet battle with dysthymia—persistent, low-grade depression. The book’s paradoxical title instantly sparked curiosity worldwide, merging the rawness of suicidal ideation with the everyday craving for Korea’s iconic spicy rice cakes. In this article, we explore why the memoir resonates so deeply, how tteokbokki becomes an unlikely lifeline, and what lessons readers can carry forward.

What Is “I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki”?

Published in 2018 and translated into multiple languages by 2022, Baek Se-hee’s book unfolds as a dialogue: her words, her therapist’s responses, and layers of internal monologue. Rather than offering neat conclusions, the author invites us to eavesdrop on her confusion, defense mechanisms, and fleeting pockets of joy. The structure feels intimate, even voyeuristic, yet profoundly validating for anyone who has ever quietly asked, “Is something wrong with me— or is this just life?”

The Meaning Behind the Title

At first glance, the title sounds contradictory. In Korean culture, tteokbokki is affordable street food you can order at any hour. By juxtaposing a death wish with a craving for comfort food, Baek encapsulates the push-and-pull of living with depression: the mind says “give up,” while the body still longs for warmth, spice, and connection. The title also disrupts romanticized portrayals of mental illness, grounding despair in an everyday setting—a plastic chair at a stall, chopsticks in hand.

Key Themes

Depression and Dysthymia

Unlike episodic major depression, dysthymia lingers quietly, often escaping clinical attention. Baek describes feeling “not sick enough” to seek help, yet too exhausted to participate fully in life. Her candid admissions of envy, self-criticism, and emotional numbness shine a light on symptoms that many readers may recognize but struggle to name. By sharing therapy notes, she demystifies psychological treatment and affirms that progress rarely feels linear.

Food as Grounding

Tteokbokki anchors the narrative whenever existential dread threatens to spiral. The dish’s chewy rice cakes and fiery gochujang sauce offer sensory immediacy—taste, smell, heat—that pulls Baek back to her body. For readers, the motif underscores how everyday rituals, from brewing tea to walking a dog, serve as micro-acts of survival. The book does not glamorize binge eating; instead, it highlights mindful nourishment as a bridge between despair and living.

Why the Book Resonates Globally

International audiences may not have grown up snacking on tteokbokki, but the memoir’s emotional core transcends borders. Many millennials and Gen Z readers face relentless productivity culture, social-media comparison, and economic precarity—conditions ripe for low-grade depression. Baek’s matter-of-fact tone rejects both self-pity and toxic positivity. By normalizing mixed emotions—wanting to die and wanting a snack—she creates space for nuance that Western discourse often overlooks.

Tteokbokki: More Than Comfort Food

Brief History of Tteokbokki

Tteokbokki dates back to Korea’s royal courts, where rice cakes were stir-fried in soy sauce. The modern, bright-red version emerged in the 1950s when street-food vendors added gochujang to stretch limited rations after the Korean War. Today you can find endless varieties—cheese, ramen, even truffle oil—yet at its core, tteokbokki represents resilience: transforming humble ingredients into something boldly flavorful.

Simple Home Recipe to Try

If Baek’s memoir leaves you craving your own bowl, here is a quick outline: Soak 300 g of cylinder rice cakes in warm water for ten minutes. In a pan, stir-fry one tablespoon of oil with sliced fish cakes, cabbage, and scallions. Add 2 cups of anchovy broth, 2 tablespoons gochujang, 1 tablespoon soy sauce, 1 teaspoon sugar, and a dash of garlic. Simmer until the sauce thickens and the rice cakes turn glossy. Top with sesame seeds and, if you like, a hard-boiled egg. The process takes 15 minutes—just long enough to practice mindful breathing between steps.

Takeaways for Readers Struggling with Mental Health

Baek Se-hee never pretends that therapy, medication, or spicy food will “fix” everything. Her biggest insight is permission: permission to feel dull, to ask for help, to crave small pleasures even while darkness hovers. Readers can adopt tangible strategies from the book: keeping a mood log, reframing catastrophic thoughts, and finding a low-stakes ritual (like cooking) that signals safety to the nervous system. If suicidal thoughts intensify, the memoir’s pages reinforce a crucial truth—seeking professional care is an act of courage, not failure.

Conclusion

“I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki” succeeds because it honors complexity. Life can taste sweet, spicy, and painfully bitter in a single bite—much like the famous dish. By documenting therapy in real time, Baek Se-hee dismantles stigma and offers a realistic roadmap: not a perfect cure, but a daily commitment to stay curious about one’s own mind. Whether you pick up the memoir for literary merit, mental-health insight, or culinary intrigue, one thing is clear: you will close the book hungrier—for authentic conversation, for compassionate self-talk, and yes, perhaps for a steaming bowl of tteokbokki.