Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell: The Brontë Sisters’ First Published Book

Explore the origins, themes, and legacy of Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, the Brontë sisters’ daring 1846 poetry debut.

Introduction to a Pseudonymous Masterpiece

Before Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, or Agnes Grey captivated Victorian readers, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë launched their literary careers with a slim, privately printed poetry collection entitled Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Published in 1846 under carefully chosen male pseudonyms, the volume was meant to conceal the authors’ gender and preserve their anonymity in a literary marketplace skeptical of women’s intellectual ambitions. Today, this modest book is celebrated as the Brontë sisters’ audacious debut, laying bare their creative voices and foreshadowing the emotional power that would soon redefine English fiction.

The Story Behind the Publication

In the isolated parsonage at Haworth on the Yorkshire moors, the three sisters wrote constantly, driven by imagination and a shared belief in the transformative potential of literature. Charlotte discovered an advertisement for a vanity press firm, Aylott and Jones, which offered to publish books at the author’s expense. Determined to test the waters, the sisters pooled their savings and submitted a manuscript containing twenty-one of Emily’s poems, nineteen of Anne’s, and nineteen of Charlotte’s, arranging them alphabetically by pseudonym. The book appeared in May 1846, bound in drab cloth and priced at four shillings. Only two copies sold within the first year, a disappointing outcome that nonetheless steeled the sisters’ resolve to write novels—ventures that would soon eclipse their poetic experiment.

The Choice of the Bell Pseudonyms

Why Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell? The invented surnames share the same initial letter as Brontë, while the first names echo the sisters’ own: Charlotte became Currer, Emily transformed into Ellis, and Anne adopted Acton. The masculine façade allowed them to sidestep prevailing prejudices that labeled women’s writing as sentimental or trivial. In a later preface, Charlotte explained that the trio “had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.” The choice exemplifies the tightrope Victorian women walked between creativity and respectability, and it reveals the Brontës’ pragmatic strategy for gaining a hearing in a competitive, male-dominated field.

Themes and Stylistic Signatures

Though united in publication, the poems showcase three distinct sensibilities. Emily’s verses stand out for their elemental force: she summons storms, night skies, and lonely winds to probe freedom, death, and the soul’s yearning for transcendence. In lines like “No coward soul is mine,” she rejects earthly confines with austere grandeur reminiscent of Byron yet unmistakably her own. Anne’s poems, gentler in tone, meditate on faith, compassion, and the fragile dignity of the oppressed; her keen social conscience anticipates the reformist themes of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Charlotte’s contributions display technical polish and dramatic flair, often adopting narrative voices that grapple with ambition, remorse, and unrequited love. Together, the collection ranges from ballad forms to lyric odes, bound by vivid natural imagery and a shared insistence on emotional authenticity.

Critical Reception in the Nineteenth Century

Contemporary reviews were few, yet not entirely unfavorable. The Athenaeum noted “power and originality” in many pieces, while also faulting the collection for “harshness” and “obscurity,” critiques frequently leveled at Romantic inheritors who resisted polished propriety. Sales, however, languished. Only when the sisters’ novels achieved sensational success in 1847–48 did unsold copies of the poetry gain value as literary curiosities. Charlotte attempted a second edition in 1850, appending previously unpublished poems by Emily and Anne and penning an explanatory biographical notice that, for the first time, revealed the Bells’ true identities to the public.

Legacy and Modern Influence

Today, Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell is recognized as a landmark in women’s literary history and in the evolution of Victorian poetry. Scholars trace Emily’s radical imagery forward to modernist experimentation, while Anne’s moral clarity resonates with contemporary conversations about gender equity and social justice. For readers, the volume offers a rare glimpse into artistic formation: motifs that dominate the sisters’ later novels—windswept landscapes, moral rebellion, and feminist defiance—appear here in concentrated lyrical form. The poems also contribute to a broader reassessment of nineteenth-century women’s poetry, a field once overshadowed by the male Romantic canon but now central to classroom syllabi and literary anthologies.

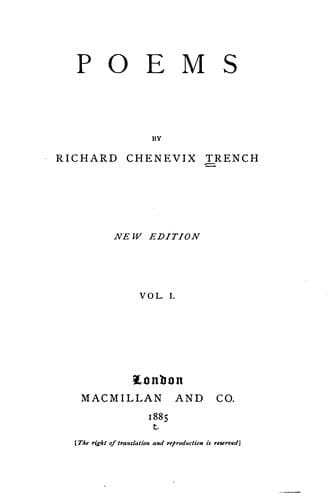

Where to Read the Collection Today

Because the original print run was limited to roughly 1,000 copies, surviving first editions are prized by collectors and institutions such as the Brontë Parsonage Museum and the British Library. Fortunately, digital facsimiles and modern reprints make the text widely accessible. Reputable options include the public-domain scans available through Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive, as well as scholarly editions from Oxford World’s Classics and Penguin, which feature helpful notes and contextual essays. Reading the poems alongside the sisters’ letters, juvenilia, and novels enriches appreciation of their interwoven creative journey.

Tips for Teaching or Studying the Poems

Educators often pair Emily’s “Remembrance” with her later poem “Cold in the earth” to explore evolving elegiac techniques, or contrast Anne’s “Home” with Charlotte’s “Pilate’s Wife’s Dream” to discuss differing religious perspectives. Another fruitful activity is mapping recurring natural images—moors, night skies, and changing seasons—across the three poets to reveal shared environmental influences and individual thematic spins. Because the Brontës wrote during the shift from Romanticism to Victorian realism, placing the poems alongside works by Wordsworth or Tennyson encourages lively discussion about continuity and innovation in nineteenth-century verse.

Conclusion: Why the Bells Still Ring

Although overshadowed by the thunderous fame of their novels, the Brontë sisters’ inaugural publication remains a resonant testament to artistic courage. In choosing pseudonyms, they challenged gendered barriers; in sharing deeply personal verse, they entrusted readers with their innermost convictions. Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell endures not merely as a historical artifact but as living literature—its rhythms echoing across classrooms, libraries, and digital screens, inviting each new generation to feel the sweep of moorland winds and the restless surge of imaginative freedom.