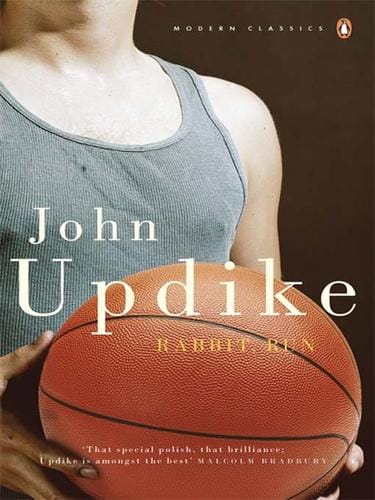

Rabbit, Run: John Updike’s Timeless Portrait of Restless America

A deep dive into John Updike’s Rabbit, Run, covering its plot, themes, characters, and lasting influence on modern American literature.

Introduction

John Updike’s 1960 novel Rabbit, Run is routinely cited as one of the most incisive portrayals of post-war American malaise. Centered on the aimless flight of former high-school basketball star Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, the book captures a nation caught between the security of the 1950s and the social upheavals that would define the 1960s. More than six decades later, the novel still resonates because it examines universal questions of freedom, responsibility, and the elusive nature of happiness. This article offers an 800-word exploration of the plot, characters, themes, and lasting cultural impact of Updike’s seminal work.

Plot Summary

Set in the fictional city of Brewer, Pennsylvania, Rabbit, Run opens with twenty-six-year-old Harry Angstrom making a routine stop at a street corner where kids play pick-up basketball. Briefly reliving his high-school glory, he feels a jolt of nostalgia that contrasts sharply with the claustrophobia of his current life: a dreary sales job, a cramped apartment, and a pregnant wife, Janice, who has drifted into alcoholism. In a moment of panic, Rabbit gets in his car and drives south, hoping distance will clarify his restless discontent. The journey, however, is less a geographic escape than a psychological odyssey. He soon returns to Brewer, embarks on an affair with a part-time prostitute named Ruth, and oscillates between the two women as his sense of duty battles his appetite for personal freedom. Tragedy strikes when Janice, drunk and overwhelmed, accidentally drowns their infant daughter. Haunted by guilt yet still unable to submit to domestic stability, Rabbit continues to run—both literally and metaphorically—leaving readers to ponder whether his flight is brave, selfish, or simply human.

Character Analysis

Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom is at once ordinary and emblematic, an Everyman whose wild impulses are magnified by Updike’s meticulous prose. His restlessness springs from a fear of spiritual suffocation, a terror that life’s possibilities are narrowing too quickly. Yet, Rabbit’s charm and athletic grace coexist with immaturity and an almost infantile entitlement. Janice Angstrom, often viewed only through Rabbit’s critical eyes, emerges as a tragic counterpoint, her vulnerabilities accentuated by social expectations of suburban motherhood. Ruth, meanwhile, serves as both refuge and mirror, exposing Rabbit’s selfishness even as she craves connection. Secondary characters like Reverend Eccles and Rabbit’s in-laws illustrate the broader community’s attempt to impose order on chaos, emphasizing the tension between individual desire and societal norms.

Major Themes

Freedom versus Responsibility: Rabbit’s impulse to flee domestic life highlights the universal tension between personal liberty and the obligations that come with adulthood. Updike refuses easy judgments, forcing readers to wrestle with the costs of both staying and leaving.

Spiritual Emptiness: Though post-war America enjoyed unprecedented prosperity, Updike reveals an undercurrent of existential void. Rabbit seeks transcendence—through sex, running, or basketball—yet each attempt leaves him unfulfilled.

Gender and Domesticity: The novel scrutinizes mid-century gender roles, portraying Janice’s confinement within the home and Rabbit’s expectation of female caretaking. Their tragedy suggests that the traditional nuclear family can suffocate all involved when empathy is absent.

Search for Identity: Rabbit’s crises are amplified by his lingering self-image as a high-school hero. Updike makes the haunting suggestion that America, like Rabbit, is perpetually stuck in adolescence, unable to reconcile its ideals with messy realities.

Literary Style and Technique

Updike’s prose is renowned for its sensual detail and rhythmic elegance. He renders the ordinary—filling a gas tank, eating a cheeseburger—with almost sacramental significance, reaffirming his belief that beauty can be found in the mundane. The novel’s close third-person narration slips seamlessly into Rabbit’s consciousness, allowing readers to experience his impulsive decisions in real time. Updike’s use of present tense, unusual for literary fiction of the era, amplifies the urgency of Rabbit’s movements and underscores the novel’s thematic focus on living in the moment. Biblical allusions—particularly to the prodigal son—add theological depth, while subtle symbolism, like the repeated imagery of running water, foreshadows the drowning tragedy and evokes the possibility of both purification and peril.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

Rabbit, Run was controversial upon release, praised for its stylistic brilliance yet criticized for explicit sexuality and perceived amorality. Over time, however, it has become a cornerstone of modern American literature, spawning three sequels that trace Rabbit’s life through subsequent decades. The tetralogy offers an unparalleled longitudinal portrait of a single character and, by extension, the nation itself. Academics cite Rabbit as an archetype of white male disaffection, influencing later authors like Richard Ford and Jonathan Franzen. The novel’s depiction of suburban ennui has permeated film and television, from American Beauty to Mad Men. Moreover, its unflinching exploration of adult dissatisfaction anticipated the confessional tone of late-20th-century fiction, paving the way for more candid examinations of marriage, sexuality, and faith.

Conclusion

More than sixty years after its publication, Rabbit, Run endures because it confronts the messy contradictions at the heart of the American dream. Harry Angstrom’s flight is both lamentable and understandable, reflecting a restless spirit that refuses to be neatly categorized. Updike’s masterful blending of lyrical language, psychological nuance, and social critique ensures that the novel remains relevant to successive generations. Whether readers sympathize with Rabbit or condemn him, they cannot ignore the uncomfortable questions his journey raises about freedom, commitment, and what it truly means to be alive. In revealing the depths beneath suburban surfaces, Updike not only chronicled his era but also captured a timeless human struggle.