Understanding the Baroque: Art, Architecture & Music

Explore the dramatic world of Baroque art, architecture and music, uncovering its origins, signature traits and lasting impact.

What Is the Baroque?

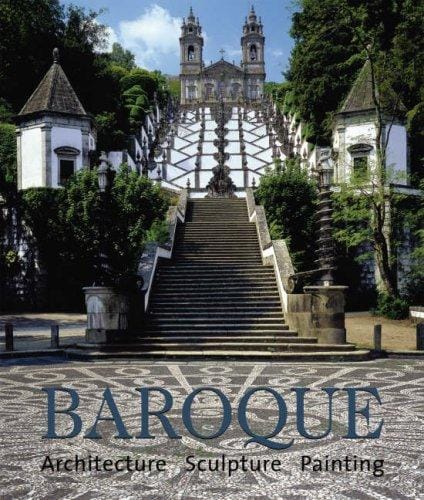

The word “Baroque” comes from the Portuguese term barroco, meaning an irregular pearl. In cultural history it identifies a stylistic era that flourished roughly between 1580 and 1750 across Europe and, through colonial expansion, the Americas. Marked by drama, emotion and lavish detail, the Baroque period transformed painting, sculpture, architecture and music into vehicles for vivid storytelling and spiritual persuasion. Whether you picture the swirling ceiling of a Roman church or the intricate fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach, Baroque creativity still captivates audiences centuries later.

Historical Background

The Baroque emerged in Rome at the end of the Renaissance, a time when the Catholic Church sought to re-energize faith after the Protestant Reformation. Artists such as Caravaggio and architects like Gian Lorenzo Bernini were commissioned to create works that spoke directly to worshippers’ hearts. Their success triggered a continental wave: Spain, France, the Spanish Netherlands, Germany and even colonial Latin America adopted the new aesthetic, adapting it to local tastes and political agendas. By the late 17th century the style had reached its zenith, touching royal courts and urban centers alike.

Key Characteristics of the Baroque Style

Despite regional differences, Baroque works share a recognizable visual and auditory vocabulary aimed at engaging the senses and stirring emotion.

- Movement and dynamism: twisting bodies, spiraling columns, melodic sequences that feel unpredictable yet logical.

- Contrast: stark chiaroscuro in painting, sudden shifts in musical texture, alternating convex and concave architectural surfaces.

- Ornamentation: gilded stucco, intricate woodcarving, virtuosic instrumental passages.

- Grandeur and scale: vast domes, monumental canvases, multi-choir compositions designed for large cathedrals.

- Emotional immediacy: facial expressions, dramatic narratives, harmonic tension resolving into release.

Baroque Painting & Sculpture

In visual art, Baroque masters rejected the intellectual calm of High Renaissance balance in favor of theatrical storytelling. Caravaggio pioneered the use of tenebrism—violent contrasts of light and shadow—to spotlight key figures and intensify moral messages. Artemisia Gentileschi’s heroines bristle with psychological depth, while Peter Paul Rubens infused mythological scenes with muscular bodies and swirling drapery. Sculpture too turned kinetic: Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa captures the climactic moment of divine union as marble seems to melt into soft flesh and fluttering cloth, all illuminated by hidden windows for celestial effect.

Baroque Architecture

Architects employed spatial illusion and decorative excess to guide viewers through carefully orchestrated experiences. The Church of Il Gesù in Rome set the template with a single nave directing attention to the altar, but it was Bernini and Borromini who pushed boundaries. Bernini’s colonnade embracing St. Peter’s Square symbolizes the church’s open arms, while Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane twists geometric forms into an undulating façade. In France, Louis XIV harnessed Baroque splendor at Versailles to project absolute power; mirrored halls, fountain-lined gardens and painted ceilings merged politics, mythology and nature into one breathtaking statement.

Baroque Music

Musically the era introduced tonal harmony and forms that remain foundational. Composers such as Claudio Monteverdi bridged Renaissance polyphony and the new style, inaugurating opera with L’Orfeo. Johann Sebastian Bach perfected the fugue and cantata, Antonio Vivaldi codified the concerto, and George Frideric Handel turned biblical epics into stage sensations with oratorios like Messiah. Instruments evolved—violins gained prominence, pipe organs expanded, and the harpsichord provided rhythmic drive. Ornamentation, basso continuo and terraced dynamics created rich textures that matched the opulence of contemporary architecture.

Global Reach and Regional Variations

Beyond Europe, Baroque aesthetics traveled along trade routes and missionary networks. In colonial Mexico, indigenous artisans blended European iconography with local motifs, producing polychrome altarpieces glowing with turquoise and gold. The Brazilian city of Ouro Preto showcases steep-roofed churches filled with carved angels by Antônio Francisco Lisboa, known as Aleijadinho. Even in Protestant Northern Europe, where religious imagery was restricted, secular palaces like Charlottenburg in Berlin adopted exuberant stuccowork and mirrored halls for princely display.

Legacy and Influence

Although the 18th-century Enlightenment favored restraint and reason, Baroque vitality never disappeared. The Neoclassical reaction provided a momentary calm before Romantic composers rediscovered Baroque intensity. In the 20th century, historically informed performance practices revived interest in period instruments and authentic ornamentation, adding fresh relevance to Bach and Vivaldi. Contemporary filmmakers, videogame designers and fashion houses routinely mine Baroque visuals for atmosphere—think lavish costume dramas or cathedral-like runways—proving the style’s enduring power to seduce the senses.

Conclusion

The Baroque period stands as a testament to art’s ability to move people emotionally, spiritually and politically. Its fusion of dynamic movement, opulent detail and narrative clarity created a language that transcended borders and mediums. Whether you gaze at a gilded altar, walk beneath a grandiose dome or listen to a crystalline harpsichord, you are participating in a centuries-long dialogue between artist and audience. Understanding Baroque principles not only enriches our appreciation of the past but also illuminates the ongoing human desire for beauty, drama and connection.