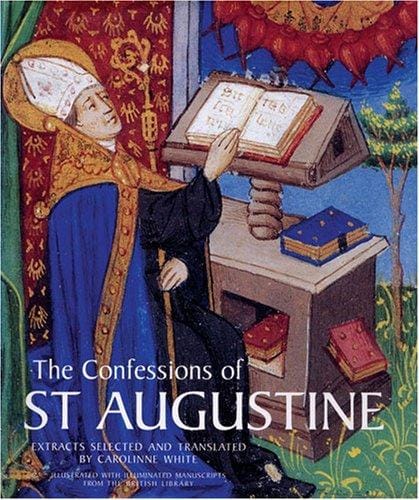

Understanding "The Confessions of St. Augustine": A Journey of Faith and Self-Discovery

Explore The Confessions of St. Augustine—its structure, themes, and lasting influence—and discover why this 4th-century spiritual memoir still speaks today.

Introduction: Why Read The Confessions Today?

Few spiritual autobiographies have influenced Western thought as profoundly as The Confessions of St. Augustine. Written between 397 and 400 CE, the thirteen-book narrative traces Augustine’s restless search for truth—from a pleasure-driven youth in Roman North Africa to his dramatic conversion to Christianity. Modern readers continue to find resonance in Augustine’s raw honesty about temptation, doubt, and the longing for meaning. By exploring how one of history’s greatest theologians confronted his flaws, we also confront our own. This article unpacks the work’s background, themes, and enduring impact for a contemporary audience.

Historical Context and Composition

Augustine penned Confessions after becoming Bishop of Hippo, a coastal city in present-day Algeria. Rome’s imperial order was crumbling, and the emerging Church faced heresies, political upheaval, and moral uncertainty. Against this backdrop, Augustine decided to dramatize his interior conversion as both a defense of Christian faith and an invitation to personal transformation. The text blends autobiography, theology, prayer, and philosophical reflection—an innovative form that broke from the stylized, triumphalist memoirs of Roman elites. Written in Latin yet laced with scriptural echoes, the book demonstrates how classical rhetoric could serve the gospel.

Structure of the Thirteen Books

The first nine books narrate Augustine’s life from infancy to the death of his mother, Monica. Books ten to thirteen shift from narrative to meditation: Augustine examines memory, time, and biblical creation to show how God’s presence permeates every facet of existence. This deliberate structural turn—biography moving into theology—signals Augustine’s conviction that the purpose of telling his story is ultimately to praise God, not himself. Readers should not be surprised when the prose morphs from anecdote to soaring prayer; the oscillation between confession of sin and confession of praise defines the entire work.

Key Themes Worth Noting

Restless Heart

Perhaps the most quoted line is the opening prayer: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.” This restlessness propels Augustine through various philosophies—Manichaeism, Neoplatonism, Skepticism—before he finds spiritual home in Christianity. The confession that worldly achievements cannot satisfy the human heart remains compelling in an age of endless distractions.

The Nature of Sin and Grace

Augustine does not glamorize his youthful escapades. He recalls stealing pears “not for hunger but for mischief,” illustrating how sin is a distortion of good desires. Yet he also depicts grace as an unmerited gift that gently overtakes the will. His wrestling with the paradox of free will versus divine sovereignty laid groundwork for later theological debates on predestination.

Memory and Self-Knowledge

In book ten Augustine turns inward, mapping memory’s “vast palaces.” He posits that remembering our past—both glory and shame—opens a doorway to knowing God, because the Imago Dei is etched within. Contemporary psychology similarly recognizes the healing power of narrative self-reflection, underscoring the text’s psychological depth.

Time and Eternity

Augustine’s meditation on time in book eleven anticipates modern philosophy. He asks, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain it, I know not.” For Augustine, time is a stretch of the soul: the present is a knife-edge where memory and anticipation meet, all held within God’s eternal ‘now.’

Influence on Christian Thought and Beyond

Confessions shaped medieval spirituality, informing monastic practice with its emphasis on interiority. During the Reformation, Martin Luther and John Calvin cited Augustine’s defense of grace as foundational. In literature, Dante, Petrarch, and later T.S. Eliot echoed Augustinian motifs of pilgrimage and self-scrutiny. Even secular thinkers—from Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Sigmund Freud—adopted the confessional mode Augustine pioneered. The work’s fusion of narrative and introspection effectively invented what we now call the psychological memoir.

Reading Tips for Modern Seekers

1. Choose a recent, readable translation, such as Sarah Ruden’s or Maria Boulding’s, which preserve Augustine’s poetic cadence without archaic English.

2. Read slowly and aloud. The book originated as an oral performance; sound amplifies its rhetorical power.

3. Keep a journal. Responding to Augustine’s questions—What do I love? Whom do I serve?—turns reading into dialogue.

4. Supplement with secondary sources. A brief commentary can clarify historical references and philosophical terms.

5. Embrace the prayers. Even if you are not religious, the liturgical cadences reveal Augustine’s emotional landscape.

Common Misconceptions

Some dismiss Confessions as gloomy or anti-body. In truth, Augustine critiques disordered desire, not desire itself; he affirms embodied life as “good” because God created it. Others label him anti-intellectual, yet he continually celebrates reason as a divine gift. Recognizing these nuances guards against caricature and allows a richer encounter with the text.

Conclusion: A Timeless Invitation

Over sixteen centuries later, The Confessions of St. Augustine still invites readers into a sacred conversation about identity, purpose, and the transcendent. Augustine’s willingness to bare his soul—admitting pride, lust, and grief—creates a mirror in which we discern our own struggles. His journey does not end in self-absorption but in worship, reminding us that the ultimate aim of self-knowledge is love of God and neighbor. Whether you approach the book for its literary artistry, historical significance, or spiritual insight, it remains a luminous guide for anyone seeking rest for a restless heart.